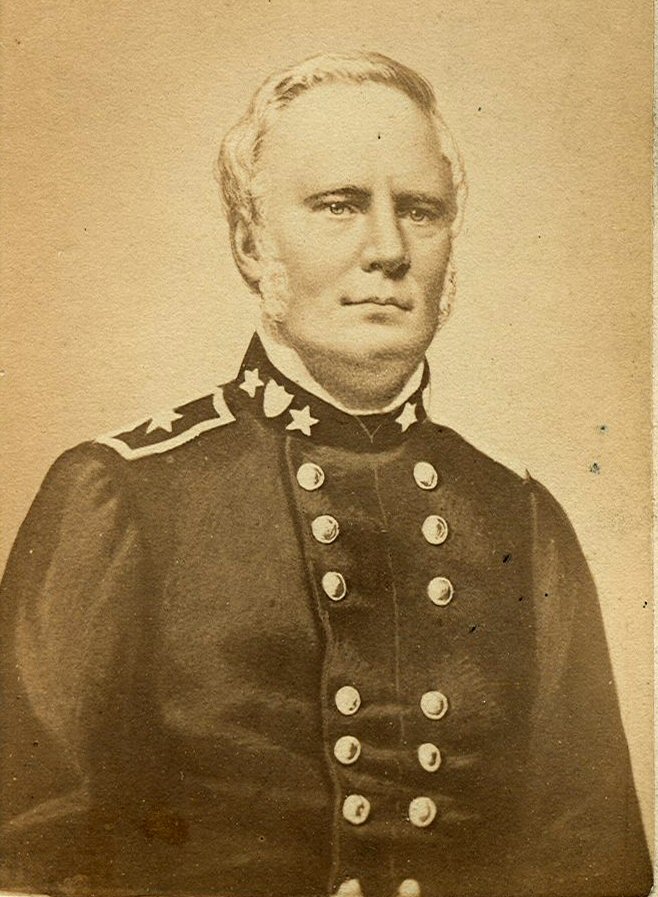

And I remember most clearly that the idea of the novel is, after all, a rather recent human invention. Anyway I’ve never been too good at being conventional, and increasingly I’ve been asking myself: Why should I restrict my own grand vision in this novel to conform to and appease the stodgy, somnolent expectations of others? I’ve been thinking lately about Herman Melville and Walt Whitman and Thomas Pynchon and especially about James Joyce. Trying to squeeze all of this into the conventional forms of the novel is a tight and constraining fit. What I mean is that there is a massive impulse at work in this novel to try to get deep into the engines of history, and specifically to give a comprehensive accounting of why America is, in the present, the country that she is. It’s occurred to me in the last couple of days, although the dissatisfaction has been growing incrementally for some time, that the novel as written is not sufficiently outrageous. Whether that was lucky for the state is for others to decide, although I certainly have my own opinion.īut also I confess that my conception of the basic structure of the novel is shifting, too. When he was lucky his fortunes, and those of the state of Missouri, rose when his luck ran out he fell, heedless of, and disavowing any responsibility for, the ruination that littered his wake. Sterling Price was all about Sterling Price and no one else. But on closer inspection in the present, as in the 1860s, we discover occasionally that presumed philanthropic impulse is sometimes simply absent. I see lingering bits of him in the present, peering out gluttonously from behind the pig-eyes of the privileged occupying positions of power, they whose only allegiance is to advancing their own status at the expense of all the subordinates and underlings who are depending on them for a certain minimum degree of wisdom and guidance. However, the more I’ve read and learned about him, and the deeper I’ve read between the lines, the more I’ve come to despise Price. Although Price fought for the rebels and Old Tom for the Federals, I’d long hoped to learn to admire Price. Price figures prominently in the Missouri Civil War saga, and in a few decades preceding, and a synchronism entangles his life and times with those of one of the characters of Memphis Blues Again, Old Tom, as well as his distant descendant, Max Bainbridge as such, coming to terms with Price is relevant to the novel’s conception and construction.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)